How to best guide your people to work together to fulfill your shared mission.

An integrative and practical approach to defining organizational values.

One of the most confusing and ignored elements of an organization’s identity can be its set of values. Most leaders say they’re important, but few can communicate why. Even fewer have created a set that has real practical impact within the organization, which I measure by how much they have been incorporated into organizational processes and are referenced by employees in real work situations.

If you randomly Google 10 companies, you’re likely to find 10 different approaches to values—a different number of values, parts of speech, and lengths of descriptions. So what’s the point of values? What do they actually do? They can be the most ambiguous, and as a result, the most ignored part of an organization’s identity. I propose, however, that they are the most vital because they created the necessary center focus from which people in the organization behave, and they build a bridge between mission, strategy, and operations.

As we begin laying out our recommended values framework, I want to start by defining an organizational value. An organizational value is a shared belief around human connection and action that produces a mission-impacting result. It answers the question: How do we choose to work together to fulfill our mission?

Let’s break this down. A shared belief is important because we’re not looking for compliance, but rather enrollment. We want our values to be so embodied that stakeholders are magnetically attracted to the organization’s culture. Values as belief-driven actions are so much more powerful than compliance-driven ones because there’s positive motivation and energy behind them instead of least common denominator passivity.

A value also communicates how individuals will work with themselves and others, clearly defining the organization’s expectations for human connection.

And finally, these belief-driven actions are not disconnected from the rest of the organization’s identity. They are pointed in a specific direction—mission fulfillment. They drive mission-fulfillment because they help communicate the organization’s core strategic elements—its competitive differentiation, business model driver, and brand promise.

Now that we’ve unpacked what defines an organizational value, and before we describe the values unique to our organizations, I want to take a quick step back. It’s vital to screen all leaders, employees, partners, vendors, board members, and anyone else you’re choosing to connect with the organization for a basic set of healthy human characteristics. These three characteristics create the possibility that your stakeholders will be able to engage in healthy ways to embody, align with, and engage in healthy conflict around the organization’s values. These non-negotiables of human behavior were well laid out by Patrick Lencioni in his book The Ideal Team Player. He calls them humble, hungry, and smart. I like using the following nouns to describe these non-negotiable characteristics—humility, emotional intelligence, and drive.

Regardless of the form and words, if our leaders and employees, candidate employees, partners, vendors, or others we are in relationship with don’t have or exhibit these characteristics from a place of neutral to positive health, we either shouldn’t enter into a relationship in the first place, or if we already are, we should directly address the situation. If any of us begin to exhibit unhealthy behaviors that are counter to these characteristics, we need to call each other out immediately and move back toward health. No one can afford to mess around with these. They are characteristics of healthy humans.

Only from that base level of healthy work-life values, then, do we move on to our organizational values framework, which contains three interdependent categories of values that are unique to each organization:

Foundational values

Detracting values

Advancing values

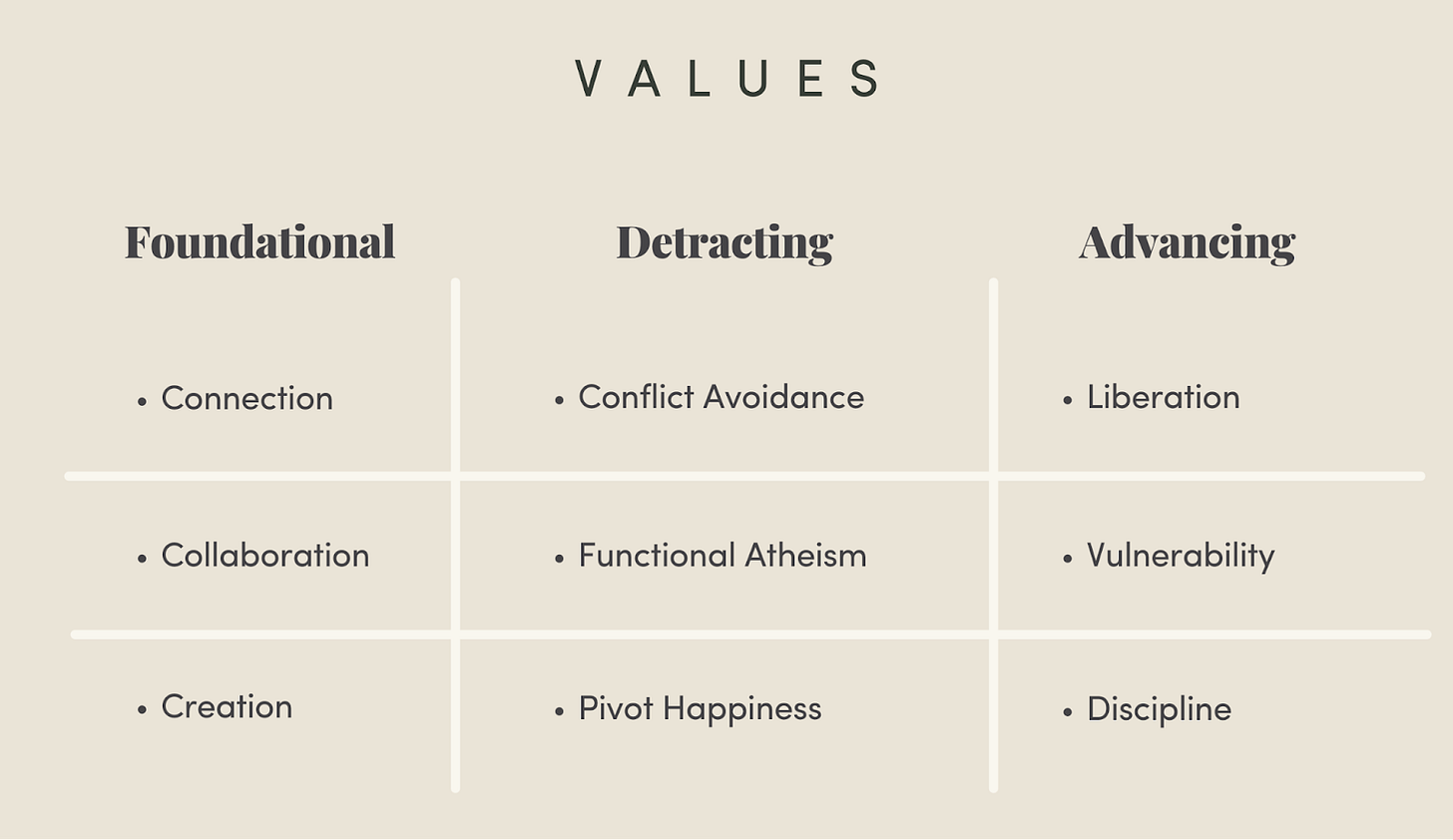

I recommend starting by identifying three foundational values and then identifying a related detracting value for each and then a related advancing value for each. At the end, you’ll have three of each value type, and you’ll also have three sets of values that are interrelated. Don’t worry if this seems confusing now. It will become more clear by the end.

Let’s start by identifying a set of your own unique foundational values. Others may call these core values, but I like to use the word foundational for a couple of reasons. First, these are often established very early on in the organization’s life by its founders. If you’re around any of the work we do in Formation Community, you’ll have heard one of our foundational beliefs—every organizational strength and weakness is rooted in the hearts of its founders or leaders. There’s a sky and a ceiling to an organization’s health. The sky is the limit for strengths, but overuse or misuse of strengths along with our weaknesses can create ceilings that limit growth. The word foundational also communicates that we’re building something together.

Because foundational values are tied to the founders (or leaders depending on the age and complexity of the org), our identification of these values best starts with a look at the strengths and voices of those leaders. I use the 5 Voices system to identify the leadership voice order of the top leader(s) to map their natural foundational voice to a values category. People who speak Creative as their foundational voice are champions of future innovation, for example, so a value for Uniqueness will likely be present in the organization. Those who speaker Pioneer are champions of strategic thinking and achievement, so a value for Expansion or Convenience will likely show up. Connectors may bring Partnership to the table, Nurturers may bring Presence, and Guardians may bring Consistency, as examples.

Foundational values are all positive personality traits, or elements of the DNA of the organization, that you are not choosing as much as identifying. As organizations grow, healthy ones will continue to screen key leaders for their resonance with these foundational values. It’s important to note that while the organization may attract those with similar voice orders, this doesn’t mean we’re looking for homogeneity of foundational voices in our teams by any means. In fact, I’ve worked with many leaders who speak Guardian as their foundational voice, for example, who are excited for their work as a CFO or in operations in highly innovative companies because they recognize their contribution in their organizational functions are necessary to bring just the right amount of institution to organizations that might otherwise get unwieldy in their constant drive for change.

The next category of values to tease out is the detracting values category. I know this seems like an odd inclusion in a values framework. Why would we want to highlight something negative here? The answer is because we are committed to the fullness of our humanity and leadership, the strengths and their corresponding challenges—the skies and the ceilings. If we don’t recognize and address all the shared beliefs around human connection and action that produce mission-impacting results—even those that impact the mission negatively—then we will continue to accidentally employ them and wonder why we aren’t advancing toward mission fulfillment as quickly as we would like. Think of detracting values as shadow values of our foundational values or strengths. The power contained in our DNA can be overused or mis-used, and we can experience counterproductive consequences. Back to the 5 Voices, we all have a comfortability with our foundational voice, which leads to a comfortability with the use of a foundational value. But Guardians, for example, can’t live without distress in an environment run by Connectors and Creators who are over employing their value for New Ideas, constantly introducing unnecessary change and ambiguity, and not allowing processes to be established let alone work toward mission fulfillment. We call out these overuses as detracting values so we’re aware of them and can counterbalance them with our advancing values.

Advancing values serve as an aspirational extension of our foundational values and a counterbalance or correction to our detracting values. They drive us forward toward mission fulfillment. I’ve found they are best aligned with or even derived from the organization’s mission statement, and as such, they are part of the identity of the organization and usually carried into and through the organization with the founder(s) or key leaders. As a result, they are innate to the founders and necessarily aspirational for many organizational members who don’t share the founders/leaders leadership voice. They serve to align the organization’s strategy from a central set of human behaviors that result in a unique positioning in the marketplace—often called competitive strategy or competitive differentiation.

Here’s a real life example of the values system in play for Formation Community. As a founder who speaks Creator Pioneer, I’ve identified Connection, Collaboration, and Creation as three foundational values. For me, connection is a way of describing my/our natural drive for organizational and systems integrity. Collaboration describes my/our drive for systems and people to work together toward a shared goal. And Creation is my/our drive for future ideas to be realized through innovation.

These DNA driven values have a shadow side, though. I don’t enjoy dealing directly with conflict, and because I’m focused naturally more on systems than people, I can often avoid conflict and may not even realize it. Functional atheism—or a belief in practice that in order to get something done or done right I need to be involved, can result from my desire to see things done through collaboration with me instead of the healthier, empowerment-focused approach of leading others to collaborate to get things done without me needing to be in the weeds. Finally, pivot happiness is a natural but detracting result of a drive for ideation and creation. The idea of something is often more shiny and fun than the work (toil) needed to bring the idea to fulfillment as challenges are faced.

So to counter these detracting values, we first focus on liberation of leaders through a culture of high support + high expectations. I can’t as easily avoid conflict if I’m communicating high expectations and am also highly supportive of people in the process of holding them accountable. My functional atheism is countered with vulnerability, an openness to admitting mistakes and clear communication about how I’m feeling that builds trust in the team. Finally, discipline counters my tendency to pivot into the next big idea. The disciplined consistency of working processes over time to achieve goals will result in the actual creation of an idea, and it gives us a far greater likelihood of fulfilling our shared mission.

As I’ve worked within this framework, I’ve found our detracting values to be a focal point for conversation and an act of vulnerability. They have given us an approachable language to identify our natural tendencies that keep us from our best work. They allow us to laugh at ourselves a bit, because we have strong foundational language and strong aspirational language on either side of them that guide us into good work. When I have a new idea, a team member may, with a smile on their face, ask if I’m being pivot happy again or if the new idea is actually tied to our current core strategy. With this loving prompt, I can then remind myself that if I want my ideas to be created, I need to be disciplined long enough for them to be realized, and I can appropriately prioritize my exploration of the new idea.

One last note. This framework doesn’t necessarily keep departments or programs within your organization from having their own set of values related to their primary function or core work. I’d be careful about this, and I certainly wouldn’t want them to be disconnected or conflicting, but I do think at times a department may want to espouse more specific values for their work that complement the overall values of the organization. If they more specifically answer the question: “How do we best perform this function together to fulfill our mission?”, then I’d encourage the articulation of specific program values in addition to the organization’s shared foundational, detracting, and advancing values.

Please see the appendix below for a visual display of Formation Community’s organizational values, which were used as examples throughout this document. Thanks also for sharing and subscribing below.

Appendix: Sample organizational values from Formation Community, Inc.